Penrith City Local History - Business & industry - Businesses

Hotels – an overview by local historian Lorna Parr (History Conference 2002)

History of Hotels in the Penrith district

by Lorna Parr, Local Historian

From: The Makings of a History Conference, 13 April 2002

It is very difficult researching hotels:

- licenses often just say Inn e.g. Harp of Erin Western Road Penrith. That could be anywhere from St Marys to Lapstone Hill.

- Secondly, they had a great love of changing names. Its not unusual for one hotel to have had four names like the Australian at Castlereagh and the Volunteer at St Marys. Owners still think it’s cool to change a name. They recently wanted to change the name of the Red Cow.

- Lastly the families once they had a taste of hotel keeping, they stayed in the industry but to confuse us they moved about. Landers, who was Castlereagh born and bred and owned Inns there, decided to go to St Marys and even the Smith family from the Red Cow went to the Commercial and to St Marys then the Pineapple.

The hotel or Inn was an important part of the community. The unquenchable thirst for spirits was a solace to relieve the dreariness and discomfort for the poor. Then the convicts, soldiers and small settlers worked extremely hard so drink brought a type of oblivion.

Illicit stills were hard to police. Governor Hunter tried in 1796 when he ordered the destruction of all illicit stills and a licensing system be installed. This did not work.

Gov. King reported that some people were “retailing spirits at an exorbitant rate and without a license. Gov. Macquarie tried to reduce the number of licensed inns and was a bit more successful as the Rum Corps had, at that time, been returned to England.

Inns in early days were mainly to supply food, a drink, and limited accommodation for travelers and horses and to pass on news. Then sale of liquor became important. Many Inns were in private homes with sly grog shops often in the barns. These private houses were then open to the public and became public houses. Horse and coaches or wagons could only travel about 25 km a day before resting so Inns were necessary for resting both man and beast. After 1825 each licensee had to provide accommodation for at least 2 guests. From 1830 the publican was required to keep a whale oil lamp burning outside his premises from dark to dawn.

The first hotel in the district was always thought to be the Depot Inn. It was the first in Penrith town but not in our council area. The Depot inn was in High Street just east of the present Police Station – then the Court House.

It was in a house set back from the street with a shingle roof and very little garden except a huge mulberry tree. The Court House was a busy place in 1824 when Sergeant Baylis opened the Depot Inn. Sgt Baylis sold the Inn in 1830 to John Moses who immediately changed the name to Kings Head. He advertised that he had the Inn and he had every comfort – cane back chairs, metal dinner plates, wines, sauternes, clarets, port and superior champagne.

The Depot cum Kings Head was sold or leased several times and then in 1853, when William Martin bought it, he called it the Harp of Erin. Strangely enough in that male chauvinistic world of the nineteenth century many women owned, and on odd occasions ran, a hotel. Catherine Harrison had the Harp of Erin in 1855 and shortly after that in 1858 I think it closed.

As I said there was a hotel in our area before the Depot. That was the First and Last at Castlereagh. As we know there was a First and Last Hotel at St Marys later – nothing to do with the Castlereagh one.

Charles Hadley had this hotel at Castlereagh and it could possibly have been on his property at Hadley Park, which was on the main road, and I don’t think he would have built elsewhere.

On 12th April 1817 (exactly 185 years ago yesterday) he renewed a licence for the First and Last. John Jamison (a magistrate) said that Charles Hadley kept a very respectable and orderly house in this district. When he renewed his licence, Hadley stated that he conducted his business with the most punctual regularity and decorum which have annually been manifested by the entire approbation of the worthy magistrates of the district. (It seems as if he had the Inn possibly from 1815 or even earlier).

An interesting hotel in Penrith was the Coach and Horses, sometimes called Wheatley’s Hotel because Mr. Wheatley ran it – with the help of his wife. It was on the Kingswood side of Parker Street. The story goes that Mrs. Wheatley loved bushrangers – she hid them, fed them and gave them gentleman’s clothes so they could take their gold and spoils to Sydney. Mr. Wheatley objected but was too afraid to tell the police.

The marriage was shaky anyway and Mr. & Mrs. Wheatley parted. She was given a house in Penrith and a weekly allowance. He had the hotel pulled down and sold the land. I don’t know when he sold as you will hear later. Mr. Wheatley was going to Sydney one day and was thrown from his horse near Blacktown and killed.

A popular name was the Railway Hotel of Inn. There was a Railway Inn and a Railway Hotel at Emu Plains, a Railway Inn in Penrith and a Railway Hotel at St Marys. The old Western Highway has changed course over the years and it seems the Railway Inn at Emu Plains was near where the railway line crossed the highway – now Cnr Bedford and Walker Streets.

There were two Inns near the road/railway crossing at Emu Plains on Lapstone Hill – the Railway and the Emu. The Railway Inn was run by George Paul 1865 and when he died in 1879 his wife took over until 1882 when she decided to close it.

Meanwhile Mr. Cooper of the Railway Hotel (south of the Railway Station Emu Plains) heard that his license was not going to be renewed owing to the unfitness of his hostelry. He asked Mrs. Paul if he could reopen the old Inn at the foot of the mountains and start there while his was being renovated. Mr. Lumsdaine and Mr. Sykes built the new Inn (this possibly was the Orient Hotel then Nepean now O’Donoghues. After 2 years Cooper went back to the Orient but the Railway Inn carried on for a time. But in the mid 1890’s closed and was demolished.

It was to Mrs. Paul’s hotel that the horseman raced when he saw the ghost on Lapstone Hill. He raced into the bar of the Railway Inn much to the amusement of the patrons. Poor William Johnson of Penrith had been to Springwood selling vegetables, and returning home had got benighted; (which I think just means afraid of the dark) when within 100 yards of the Lapstone Bridge, which would have been Lennox Bridge he says he saw a man leaning against a rock with a swag on his back; he stopped the horse thinking the man wanted to speak to him, but in an instance the swagman had disappeared…..the large black and white dog also disappeared…

The Nepean Times of the date stated: I have made enquiries and have heard exactly the same thing has been seen several times at that spot. Johnson says he will never cross the mountains again after dark – we don’t blame him if it is likely to make him so excited again.

The Railway Inn in High Street is a bit of a problem. The report in the paper states that Matthews ran this hotel until Wheatleys closed when he went up to live with Priddles in Wheatleys old hotel. Wheatleys closed about 1860 so that would make this an older Inn. It is supposed to have been somewhere near the present Australian Arms. Perhaps the building known as Railway House was once an Inn – who knows?

The St Marys Railway Hotel is much simpler. It was north of the railway line at St Marys and began as the Shane Park Hotel in about 1868 and often called the Mud House because it was made of pise bricks. This was a popular hotel for workmen being near the railway. For many years this hotel was operated by women – this being acceptable at that time as long as she was assisted in the bar by a man. Mrs. Kays in 1885-91; Mrs. McCarron 1891-94 and the poor lady died at the hotel. It was then bought by an Irishman, Daniel McGee and his sister, Sarah and they decided to change its name. He called it the Railway Hotel. Sarah McGee was fondly called “Aunty McGee”. When the cricketers complained they had nowhere to play on Sundays, she had a cricket pitch put behind the hotel so they could play on Sunday. She was a popular person in the town.

Sarah sold it in 1914 and it continued until the Depression years of the late 1930’s when trade went right off. The owner then, William McPhee closed the hotel and purchased the Log Cabin which brings us to the Log Cabin Hotel. Where the Log Cabin Motel rooms are now – on the southern end by the river, was an early Inn. It is fairly confusing as it had many names and it is difficult to put them in order as the general public didn’t seem to keep up with the changes.

The two-storey convict built Inn was one of the earliest and best known in the district. It had a carved staircase, made by convict labour. There were wide over-hanging eaves and the many windows had small panes of glass. There were sixteen rooms in the building. A huge pepper tree grew out the front with a camping ground nearby for the teamsters who made up a big proportion of the travelers in the early days.

It began life in 1827 as I think, the Emu Ferry or Wilson’s Hotel. The reason being that Wilson ran the Inn and the ferry at that spot. He was the step-son of Josephson who built the Inn. There was no bridge across the river. It was quite profitable for Wilson to run the ferry across the river as well as run an inn because he could decide if the river was too high, low or muddy to run the ferry and in consequence he probably did a good trade.

It was 1829 I think when the name was changed to Pineapple Inn. However, when Charles Darwin stayed there in 1836 he said he stayed at the inn at Emu Ferry which could simply mean it was near the ferry. The inn was then taken over by Josephson’s real son, Henry and he changed the name to Governor Bourke. I don’t know why because it was Governor Fitzroy who stayed there. Governor Fitzroy by the way was not impressed because the host and hostess “were so ultra-republican in their independence that they did not suitably address the Governor and his lady”. Some time it was also called the George IV. By 1882 Thurston from Lemongrove bought it. He sold it to T R Smith who changed the name to Riverside. There was at that time a great competition between hotels to try to attract the sporting crowd. A big boxing tournament was held at the Riverside but it resulted in many difficulties and fights and a broken arm. This hotel advertised “one of the most comfortable and complete hostelries in the district. Steam launches and boats were available for visitors. Vehicles meet every train”.

The hotel stood vacant for many years and was demolished in 1967. Mile Franklin lived in Penrith for a short while and wrote a novel about the area. She called it Some Everyday Folk and Dawn. Although she had other names for the various places it is easy to recognize the hotels – the Red Cow as she got off the train, Tattersalls where she stayed and the Riverside where she moved to enjoy the company – especially of the grand-daughter, Dawn.

The whole of that area is now the Log Cabin Hotel. In 11925 Sir Joynton Smith, Lord Mayor of Sydney, held interests in the Carrington Hotel at Katoomba, Hydro Majestic Medlow Bath and the Imperial at Mt Druitt. On his trips back and forward he deplored the fact that he could not get ‘a decent cuppa’ in Penrith. He bought the property and opened the Log House tea room. It was extended in 1939 to become the Log Cabin Hotel with a licence. This became a popular out of town spot for Sydney siders.

In the 1940’s a railway station was built nearby – although it had limited use and was demolished after 10 years. The hotel slowly declined over the war years. In 1955 Frank and Doreen McKittrick did extensions and constructed the motel. In 1969 Mrs. McCreedy who owned the Log Cabin was fined $20 on a charge that she did sell a certain article of food – to wit, rum, which had been adulterated. It seems that the Health Inspector tested all open bottles of spirits in the hotel and found the rum bottle quite weak – in fact approximately 4% water. Mrs. McCreedy thought it was caused by evaporation but the judge thought a member of staff had been taking a nip and filling it up with water so Mrs. McCreedy was fined.

In 1800 there was one brewery in NSW and by 1890 there were 307 breweries, so Australians love of drink grew. Hand in hand with the growth in breweries was the growth of temperance societies crying ‘down with the demon drink’. The Royal Hotel in Henry Street was advertised as a Temperance Hotel until 1888 then in February 1888 the first 6d Bar was opened in Penrith at the Royal Hotel. It was quite a large hotel and very attractive. The Royal Hotel began as the Amelia Palace guest house and was enlarged to the most modern hotel in Penrith. It was a two storey brick building with verandahs all round. There were 30 rooms. Water was pumped from an underground tank to the roof and fed down. A covered wagon met every train for the convenience of travelers. The first licensee to sell drink in the 6d was John Power.

Written on the hotel business card:

Newton first discovered gravitation

Fitzroy foretold the coming storm

Jenner to the world gave vaccination;

Power first sold liquor in the purest form

The Emu Inn at Emu Plains was an interesting place. It was up where the railway and the road crossed at Lapstone Hill. It was also at one time called Fox under the Hill. A chap called Henry Hall moved to Emu Plains in 1834 and immediately started an Inn in his own name. He was also a blacksmith at the same time and had several apprentices. His apprentice Evans had the Inn in his name in 1837. The following year the authorities rejected Evans so Hall’s name appears again and in 1854 his son-in-law, John Readford took over. This was a very profitable Inn as it was right at the foot of Lapstone. Henry Hall died there in 1890. The Inn was demolished. In the 1980’s NDHS had a letter from a researched who stated she had a photo of this Inn. She said it was a large weather-board building in bad repair in 1931 when the photo was taken. There were verandahs on 3 sides and dormer windows in a steep roof and two brick chimneys at the back. Last year I tried to find that lady with the photo but couldn’t.

One Inn was kept by Jonathon Strange who was one of the 5 Cato Street conspirators. They were sent to Australia as convicts in 1820 for plotting against the British Government. Jonathon applied for his wife and four children to come out but his application was unsuccessful. In 1829 he married Jane Baylis aged 16 years (he was 39) and they had 10 children. His licence for the Mountaineer was rejected in 1837 but he stayed there for a few years. He later went to Bathurst where he acquired a lot of land and died wealthy.

There were a great number of Inns along the highway mid to late 19th century but by early 20th century hotels were common rather than an Inn. Tattersalls and the Commercial Hotel were possibly the two most luxurious in Penrith, with first class accommodation as well as meeting rooms, grand dining room and pf course the bar. The others in Penrith – the Red Cow was much frequented by railway workers, the Federal (once the Wheelwrights Arms) was again the working man’s pub. The drinkers cried into their beers the day it closed. In 1890 Patrick O’Connell was the owner. He grew a pumpkin on his farm at Castlereagh and it was 48lbs – he proudly displayed it on the counter but it disappeared. He was upset and advertised that if anyone brought it back within 2 days he would give them 10/- ($1) and some pumpkin seeds. I wonder did they.

He also advertised that he had a phrenologist there. His name was Professor P de Lissa. Mr. O’Connell thought he was great. Prof. De Lissa also took out corns painlessly and treated anything else. Eventually Prof. De Lissa was run out of town for not paying his rent.

For a time the hotel atmosphere picked up but by mid 20th century there were many “larrikins” as the paper called them – we would call them louts – hanging around the street each night. It was pulled down in 1976.

William George Jordan, a train driver purchased the block of land fr0om Woodriff in 1877, built a house and later the Tattersalls Hotel. He was also on the Council but had to relinquish that position as employees were not to hold such jobs. He leased the hotel in 1889 to Charles Amos Messenger a champion sculler who had all his trophies on display. It is not surprising that rowing club meetings were held there. William Jordan still owned the hotel and stated that it was not to be sold until his last child died. He had four children and the last to die was Mary Morrison, licensee from 1938-55.

Accommodation was one of the most important aspects of the Tatts. Luxury in the rooms. Many weddings were held there. Railway men were also catered for, with showers and plunge baths and annex quarters to stay between trains. Tattersalls was promoted as the sportsman’s hotel. The Rowing Club met there as well as many other groups. Quoits matches were held, foot races, as well as sports and dancing on the lawn. It was unfortunately demolished in the 1980’s. Tattersalls and the Red Cow were two hotels that did not have a name change.

Commercial Hotel or Hotel Penrith is the oldest hotel still being used – at one time the most important and in the most prominent position. John Perry from the Rose Inn opposite bought the land in 1851 with an old store on it and made it a hotel. He added a second storey and named it the Commercial Hotel. Perry leased the hotel to Donald Beatson but Beatson left when Perry put up the rent to a pound a day. Beatson built his own Inn, the Sterling Castle in Henry Street. In 1864, Donald Beatson bought the Commercial Hotel when Perry sold it – the Hotel and all the land back to Henry Street for £1700. Later he gave a block to Council for the first Council chambers.

Beatson served good beer and had a fine table. The hotel wagonette met trains for the patrons. Rooms ran along the main street. There was a verandah all around with greenery and ferns for coolness, also an open court which was made into a ballroom for the first Penrith Volunteer Rifles Ball.

Donald Beatson bought the billiard room next door in 1880 (after selling the Sterling Castle to the Education Dept) and added the billiard room to the hotel. The paddock behind (old library / now courthouse area) was used for emptying slops (chamber pots) – a “dying ground where sanitary matters are well provided for”.

The Commercial was renowned for the service and good meals. The Nepean Times said it wasn’t just a country Inn, it was a hotel. They also attracted sporting groups – at one time they had pigeon shooting contests at Commercial Hotel and afterwards Mr. Muriel started a Hunt Club and Mrs. Muriel led the hunt. In 1930 the name was changed to Hotel Penrith and is still operating today.

There were a great number of hotels and Inns along the Western Road – through St Marys, Penrith and Emu Plains. It was the romantic road, the road to riches, to wonderful land grants, to the gold fields and the road to freedom. There were many Inns at Castlereagh, some at Luddenham, Mulgoa and of course Wallacia. The Inn or Hotel was a place to meet friends, to have a drink or a meal, to stay the night, to exchange news, to leave the missus while you conducted business and a place to forget one’s cares and problems.

Lorna Parr

The Australian Arms Hotel, presently situated on the north-east corner of High and Lawson Streets, has a long history in Penrith. In the mid-1880’s, the site was occupied by a Thomas Andrews who operated a butcher’s shop. Andrews later opened a public house on the site – this was to become known as the Australian Arms Hotel. When Mr. Andrews died in the early 1890’s, his widow Harriett (his second wife), after keeping on the business for some time, rebuilt the hotel, but soon afterwards retired into private life. Mrs. Andrews died on 25 August 1901, at the age of 49, after a long illness. A year after her death in November 1902, the hotel was auctioned and eventually renovated by one of the new licensees, Mr. Richard Aughey.

The present building on the site was built in 1940, the old hotel being demolished. In 1960, the brewery firm Tooheys Ltd. purchased the hotel from Mr. F.G. Fulton. [Originally published in the Penrith District Star newspaper in 1984 – updated with notes in 1996.]

Up until the establishment of a locally produced newspaper, Sydney and Parramatta newspapers, such as the Evening News, Cumberland Mercury and Sydney Morning Herald circulated in the local area and carried local news reports. At each Council meeting a table and chair were provided for a reporter although the relationship with the press was not always a congenial one. At the 1 February 1872 meeting, Mayor Riley denounced an Evening News report on Council as a ‘tissue of falsehood’, advising the newspaper reporter to in future ‘be careful to report strictly the truth alone’.

It was not until the Penrith Argus and the Nepean Times were circulated that the local community were serviced with news of their district from Rooty Hill to Springwood, Castlereagh to Bringelly. The Cumberland Times and Penrith Advertiser provided some local content and was possibly only published in the 1870s. Although circulated in Penrith and St Marys, most of its content was Parramatta based. Penrith Council meetings were recorded and Alfred Colless had a substantial advertising space for his general store on the corner of High and Station Streets.

The first newspaper published in Penrith was the short-lived Penrith Argus which commenced in 1881. Newspaper proprietor, William Webb, who was born in the district, had by the 1880s established a number of country papers. He set up his apprentice, a young William Shannon Walker as editor, and William Rhodes as printer.

The Nepean Times published by Alfred Colless was the second known newspaper to be published in Penrith. After the Nepean Times appeared on 3 March 1882, the Argus lasted a few months, subsumed by October into the Nepean Times. By this time Webb was working in Penrith as auctioneer and commission agent. He was given a column in the Nepean Times, maybe as part payment for the Argus. As stated by Colless, the Nepean Times was ‘An independent organ of public opinion’.

Colless became the master of local opinion, producing a newspaper which ‘contained leading articles on prominent questions of the day, latest local news and telegrams, humourous extracts…and latest Sydney commercial news’. Published initially every Saturday the ‘popular independent organ for the people’ sold for threepence for the eighty years of its existence. Rhodes moved across to work for Colless and remained its printer for many years. Walker left the district, returning in 1898 to take over his father-in-law’s bakery.

First issue of the Nepean Times

Colless sent out the first edition of his paper to his contemporaries, publishing their positive reviews on 17 March. His aggressive newspaper reporting and editorial style saw a war of words played out between the Nepean Times and other circulating newspapers, especially the Cumberland Mercury. Colless criticised the reporting integrity of (possibly John Price) the Cumberland Mercury, who in turn made literary swipes at the Nepean Times reporters. The Cumberland Mercury also accused the Nepean Times office of editorial bias against those who chose not to use the printing facilities at the Times Office.

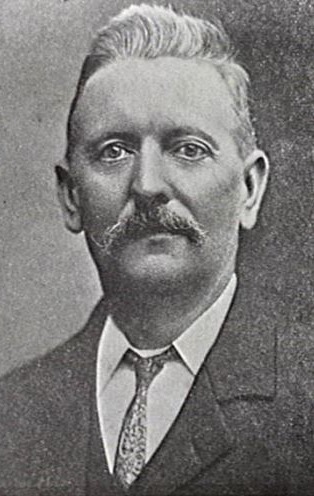

Alfred Colless

Colless established himself as an auctioneer, with a store and stationery business on the northwest corner of High and Station streets where he first published his newspaper. A few months later, the business transferred to the new Besley building further east along High Street. Thirty-year old Colless was Mayor of Penrith when he commenced the Nepean Times. He had been elected to Council in 1876 and remained until 1883. In that time he served as Mayor from 1880 to 1882.

On 28 May 1891, amidst much fanfare, George Nichols published St Marys’ first local newspaper, the St Marys Gazette. Nichols was the grandson of the colony’s first postmaster, ex-convict Isaac Nichols and Rosanna Abrahams. Nichols had practiced as a solicitor as well, at Moss Vale in the 1880s, but following his bankruptcy in 1888, relocated to the new Llandilo estate, near St Marys.

Although the newspaper’s birth was announced with enthusiasm by the Nepean Times, competition for readership and for the local Council’s advertising and stationery business soon emerged. By September, Colless launched an all out attack on the credibility of Nichols’ journalism and his ‘literary piracy’ in reporting local events.When St Marys Council rescinded their decision in favour of Colless in 1894, it must have spelt the end for St Marys’ independent newspaper. Colless purchased the St Marys Gazette in 1895. Nichols retired to his store at Llandilo and in November 1896 took over the post office.

Alfred Colless died at the end of 1920. The Nepean Times reported on 1 January 1921 ‘With the concluding days of 1920 came the close of a life that figured prominently and honorably in the history of the Nepean district’. Colless was born at Emu Plains in 1851 and was involved in every public event in the district’s history, either as an official or reporting each event in his newspaper. Businessman, journalist, and auctioneer, Colless led an active social and business life in the Nepean district. His lively editorials and his skill in recognising the important moments in the district’s history, stirred his reading public’s consciousness like no other could do.

The Nepean Times, with permission from the Colless family, was brought into the 21st century when Penrith Library funded the digitisation of the newspaper for uploading onto the National Library of Australia’s Trove site.

John Price was 31 years old when he moved to Penrith in 1855 from the Richmond area where he had previously lived and married his first wife Charlotte. An enterprising man, Price made a living as an undertaker, monumental mason, auctioneer and commission agent. His funeral business was established on the south side of High Street near Castlereagh Street. In later years, John Price’s son John Junius established a picture theatre on the site. The family lived at the same address as the funeral home until around 1862 when they moved into their new home in Henry Street, next door to the Methodist Church. In 1871 Price was appointed Penrith Municipal Council’s town clerk, its first employee. He was also for a time a reporter for the Cumberland Mercury.

Price and his wife Charlotte had eleven children. Charlotte died in 1876 and Price married local schoolteacher Elizabeth Robertson, a few months later. They had four children, Halwyn, John, Charlotte and Leopold. His death in 1893 shocked the townspeople who lined the streets by the hundreds for his funeral from his home in Henry Street to St Stephens Anglican Church and cemetery.

After the death of John Price, his wife Elizabeth continued the funeral business, located in High Street, opposite the Post Office. W. Fragar was her manager. Later her son Leopold joined the business. Relatives Nelson and Arthur Price also established a funeral home in Penrith in opposition around this time. It was located west along High Street on the north east corner with Station Street. Nelson was the son of William Robert Price and Elizabeth Young of Richmond and was a grand nephew of John Price. Nelson Price, a former railway foreman, blacksmith and farrier, had been apprenticed to William Starling and in 1894 they leased land on the corner of High and Station Streets from Francis Woodriff of Combewood.

According to the Nepean Times 15 October 1921, the exhumation of John and Mary Lees took place on 7 October 1921 at Castlereagh General Cemetery. Their bodies ‘had wilted considerably’. They were reinterred in the Methodist cemetery at Castlereagh. Everyone was there, the Constabulary (Constable Donnelly), the Clergy (Rev Samuel Roberts). The gravedigger was George Price, a nephew of John Price. George Price, who died in 1923 aged 74 years, was for many years Kingswood cemtery’s caretaker.

Exhumation of John Lees bones

The present site of John Price and Son, at the corner of Station and Henry Streets, was once the site of a livery stable business and a blacksmith’s shop. The original livery stables were operated by the Priddle family until September 1908 when Louisa Priddle sold the property to Nelson Price. He continued to operate the livery stables and blacksmith’s shop. In 1927, Nelson purchased the property he had leased from Woodriff for 700 pounds. He lived in the cottage and worked the livery next to it.

John Price & Son advertisement in the Nepean Times 1922, the year Leopold price sold to Nelson Price

Elizabeth Price died in 1920 and in August 1922 the business, John Price and Son, was taken over by Nelson Price with Leopold continuing on as undertaker and monumental mason. The business remained in High Street (opposite the Post Office) but its second address, Henry Street (the home of Leo and Essie Price) was changed to Nelson Price’s address in Station Street. Price subdivided and sold some of his property in Station Street in 1945. In the early 1940s, he moved his home and business to 480 High Street, next to Penrith Auction Mart. He died there in September 1949. A few days before his death, Nelson Price sold his properties in High and Station Streets to the Rural Bank of NSW.

John Price & Son advertisement in the Nepean Times 1930

A few months later the Rural Bank sold the property on the corner of Station and Henry Streets to William Frederick Smith of Penrith Motors. The present building was constructed some time before 1957. The business, John Price and Son was operated by Smith’s brother-in-law and sister Cecil and Vera Tierney from 480 High Street until the new funeral home was completed. Cecil died in 1957 and Vera and her relatives continued to operate the business until February 1973 when it was sold to John Lynch. Vera Tierney lived in Stafford Street and passed away in 1982. The business John Price and Son has continued to provide a service to the people of Penrith well into the twenty-first century.