Penrith City Local History - People - Health

Penrith District Dispensary and Benevolent Society and Nepean Cottage Hospital

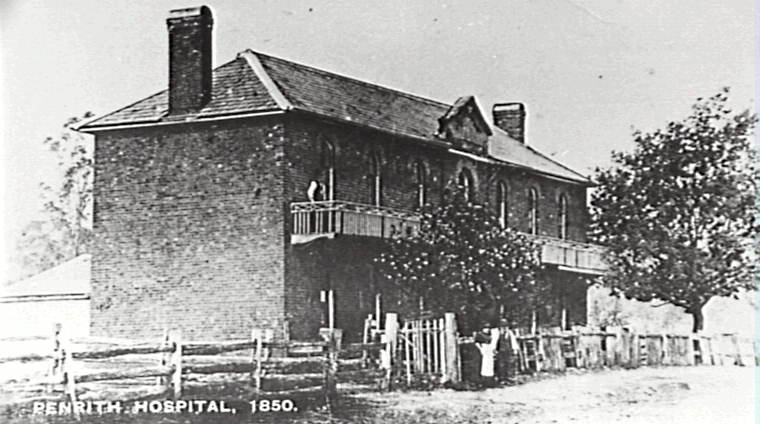

Penrith District Dispensary and Benevolent Society was formed during 1846 (exact date unknown). Its meeting place was the Court House, Henry Street, Penrith. (Location of the Dispensary unknown). It continued in existence until March 1860 when it became known as Penrith Hospital and Benevolent Society.

In March 1855 the Society resolved to expend funds to its credit on a hospital in the town of Penrith . £500 was allocated for the purpose and in July 1855 the Colonial Treasurer advised a similar amount of £500 was placed in the estimates for the erection of a hospital.

In July 1855, Captain Phillip Parker King, RN offered one acre of land to the Society for the erection of a hospital. A sub Committee selected a site on a slight rise north of the Great Western Road just prior to entry to Penrith. It was located in Henry Street on King’s sub division. When the railway cut through Henry Street , the site of the hospital was in the eastern part, now Cox Avenue (Lots 145, 147, 149).

The exact date of completion of the hospital is uncertain but the Committee inspected the building on 16 November 1857 and requested some modifications. The building was completed by 30 July 1858. It appears the hospital did not open to the public until March 1860 – medical services and furniture being organised in the meantime. The Penrith District Dispensary and Benevolent Society changed names, as indicated above, at this stage. The hospital continued in operation until late 1870 or early 1871.

Penrith’s first hospital

Penrith’s first hospital

Between the closure of this hospital and early 1890 the Nepean District had no accommodation for the relief of the sick and injured.

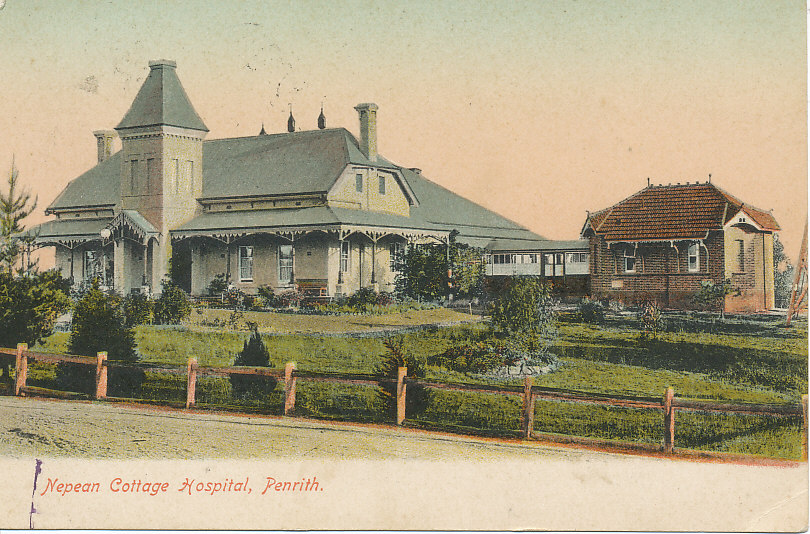

In March 1890, the premises of Mrs Price in High Street opposite the courthouse were rented for £1 per week as a hospital. On 1 April 1890, Mrs Lawrence was appointed acting matron and caretaker. On 9 April 1890 the Nepean Cottage Hospital was formally opened. In December 1892, the Committee of the Nepean Cottage Hospital accepted the offer of 3 acres at Lemongrove from the Honourable PG King, MLC.

The first cottage hospital

The new hospital was built on this site and was officially opened on 3 July 1895. The opening of the new Nepean Cottage Hospital was a most important function, and a very large crowd gathered to witness the proceedings. The memorial stone had been laid by Mrs James Ewan of Glenleigh on 19 December 1894. A gold key was presented to the President which opened the new hospital to the public for the first time. After official business preparations were concluded a first-class programme of vocal and instrumental music were enjoyed.

Nepean Cottage Hospital

Nepean Cottage Hospital

In 1904 an operating theatre was added and in 1908 property adjourning the hospital (3 acres belonging to Mr Phillips) was purchased in order that a Nurses Home could be acquired. In 1909 the new Nurses Home was opened and this was followed in 1910 by the opening of a new Isolation Ward.

The hospital was further extended in 1945 through provision of a Maternity Unit and four new cottages to house nursing staff. The future needs of the district had been under review for some time at this stage and plans were reaching finality in 1938 for construction of a new hospital. Intervention of the war delayed the planning of the project which was recommenced at the conclusion of the war and the new hospital was opened on 12 May 1956. This saw closure of the former hospital at Lemongrove.

It was initially intended that the site of the former Nepean District Hospital at Lemongrove be sold. However, it was later decided to renovate and extend the buildings on the site to provide hospitalisation for aged infirm and chronically ill persons. This is where the history of the Governor Phillip Special Hospital begins.

The buildings of the former District Hospital having been remodelled and extended, the Governor Phillip Special Hospital was officially opened on 21 July 1962 with the first patients being admitted on 1 August 1962. Upon its opening in 1962 the Governor Phillip Special Hospital consisted of 90 beds in three wings named after long-serving local doctors;

East Wing 35 beds – later named Manly Barrow Wing

West Wing 38 beds – later named Edward Day Wing

South Wing 17 beds – later named Frederick Higgins Wing

The following additions have been made since the opening of the hospital;

21 August 1965 20 bed Home Annex (W.L. Chapman Annexe)

15 June 1968 Geriatric Day Hospital

3 February 1973 The Rehabilitation Area(Adrian J Newton Rehabilitation Unit)

9 March 1974 A.M. Ross Wing – accommodating 24 patients.

Some internal modifications to the buildings have resulted in redistribution of beds throughout the hospital;

HM Ross Wing 28 beds catering for intensive rehabilitation to patients of all ages and Geriatric Assessment Services.

Manly Barrow Wing 35 beds – slow stream rehabilitation, respite/crisis care facilities, long term stay.

Edward Day Wing 31 beds – long term stay.

Frederick Higgins Wing 20 beds – long term stay terminal care beds.

WL Chapman Annexe 20 beds – persons with high level of independence not requiring constant nursing supervision.

Penrith District Registers from the Benevolent Asylum from 1847 – 1860: The register is a list of patients who were attended to at the Benevolent Asylum. The register is on on microfilm and can be viewed in Penrith City Library.

Before the First World War was officially ended, a pneumonic influenza pandemic was spreading across the world. Thought to have been spread by returning soldiers, Australia became another on a long list of countries affected by the disease. The Spanish flu, as it became known, was given the name because neutral Spain was the first to report on the devastating epidemic. The warring nations of Europe, in order to keep up morale, were loath to spread the news of an emerging pandemic. Between 50 and 100 million people would die worldwide, including 15,000 Australians, and in the space of two years this devastating disease caused at least three times as many deaths as the four years of fighting during the war.

This pneumonic influenza was caused by a highly contagious respiratory virus that filled its victim’s organs with bloody fluid and could kill within a short period of time. It also particularly affected healthy young men and women. The worst affected group were pregnant women and many of those lost their child as well. The influenza virus, even today, rapidly mutates and consequently the population cannot fully form an immunity. It was not until the 1930s that researchers established that influenza was in fact caused by a virus, not a bacterium. Although people demanded inoculation and a vaccine was produced, the bacterial vaccines developed for Spanish influenza were probably ineffective on influenza, but possibly helped with secondary infections.

As war raged across Europe and the Middle East, serving local men and women came in contact with the influenza disease, not yet considered of pandemic proportions.

Corporal Reginald Donald Joshua McLean, the son of Emu Plains Police Sergeant Samuel McLean and wife Colina enlisted in January 1916. On 6 December, McLean was admitted to hospital in Amiens with influenza. He recovered only to rejoin his battalion and on 15 April 1917 be killed in action.

Driver John Whincup from Mulgoa had enlisted on 25 September 1916. By June 1917, he was in France. On 31 October Whincup was admitted to the 41st Stationary Hospital at Dury-le-Amiens suffering from influenza which then developed into bronchial pneumonia. On 4 November 1918, he was placed on the dangerously ill list and died three days later on 7 November.

Sapper Sydney William (Billie) Bennett, the son of James and Mary Bennett, enlisted on 26 November 1917 and spent all of his service in the Middle East. By October 1918, he was with British and Australian troops that had entered Damascus. On 16 October, Bennett was admitted to hospital, suffering from malignant malaria and died on 21 October 1918. Bennett was buried the following day, alongside many, who had died from an epidemic of malaria, cholera and influenza that was sweeping through Palestine. During the second week of October, more than 1,800 new malaria infections were diagnosed and pandemic influenza had broken out. During the summer of 1918, it became apparent that when Allied troops moved into former Turkish controlled territories they would be exposed to high levels of infectious diseases. In order to prepare for this eventuality mobile diagnosis stations were formed. After treating Allied troops they were then faced with treating thousands of sick civilians and Turkish soldiers.

Private Herbert Ryan from Bailey Park St Marys, the son of John and Mary Ryan enlisted in June 1918. In September 1918, Ryan was admitted to Military Hospital at Chatham with mumps and after recovering in October, was transferred to his Training Battalion. On 29 January 1919, he was admitted to Australian General Hospital at Sutton Veny with influenza and died on 6 February.

Nurse Annie Major-West was matron at Nepean Cottage Hospital when she enlisted in May 1917. She was immediately sent to Salonika in Greece. In June 1918, Major-West was suffering from debility and sent to the Sisters’ Convalescent Camp. She returned to work in August, but in September was suffering from influenza and again admitted to hospital. On 20 September, Major-West returned to duty with the 50th General Hospital. She returned to Australia in September 1919.

Nurse Ada Alice Morehead, the daughter of John and Annie Morehead of Luddenham enlisted in July 1915. Soon after arriving in England she was posted to a number of war hospitals before her posting in January 1918 to the 5th Stationary Hospital in France. By the end of the year she was back in England and in May 1919 was found to be debilitated and suffered from influenza, coughing for three months. Soon afterwards Morehead and her sister Clara returned to Australia.

Nurse Vida Greentree, the daughter of Albert and Jane Greentree enlisted in May 1917. She was posted to Salonika in Greece and during her time there nursed many German, Bulgarian and Turkish prisoners of war. In November 1918, Greentree was transferred to the 50th General Hospital near Salonika where many of the hospital’s patients were victims of the influenza epidemic. She returned to Australia in September 1919.

Nurse Adele Baker, the daughter of Alfred and Sophia Baker enlisted in April 1917. On arrival at Salonika, she served with a number of British hospitals and in May 1918, she was admitted to the 43rd General Hospital with dysentery. After convalescing Baker resumed her nursing duties, but in August was hospitalised with influenza. In February 1919, Baker transferred to England before returning to Australia in September 1919.

In New South Wales, the first notifications of the threatened outbreak came from the Public Health Department in late November 1918, asking local councils for their cooperation in preventing the spread of the outbreak. The department also provided councils with instructions on precautionary measures. They were to register all cases of influenza in their respective infectious diseases registers. Pneumonic influenza was the only form of the disease notifiable under the Public Health Act. The registers for Penrith, St Marys and Castlereagh are now held by Penrith City Library, and are currently being transcribed. Information on the impending epidemic was also published in the Nepean Times on 30 November. People were encouraged to liberally use disinfectant, avoid crowds, keep away from ‘coughers and spitters’ and wear masks in public. At a council meeting in June 1919, Alderman David Fitch from Penrith Council stated ‘Considering the large number of people who go backwards and forwards between here and the city, I think it speaks well for the health of the town that there are so few cases’.

In February 1919, St Stephens Anglican Church organised a special service of ‘humiliation and prayer’ in connection with the outbreak. The service was arranged in the churchyard, not in the church and masks had to be worn. A free inoculation depot was opened in the old Penrith School building in Henry Street in early 1919, supervised by the government medical officer, Dr Higgins. In March, Dr Higgins reported that he had undertaken over 1000 inoculations throughout the district. Similarly at St Marys, a depot was set up with the help of Red Cross volunteers. Children attended school wearing masks and smelling of camphor. As a precaution, meetings were postponed, and theatres, hotels and churches were closed. Although the Nepean Picture Theatre was closed throughout July 1919, the flu did not stop the Penrith footballers from travelling to Richmond for a game, winning 17-nil. The Penrith players wore black armbands out of respect for one of their players, Charles Paul who had lost his wife and newborn to influenza.

Roy Dollin, a returned soldier was a son of George and Mary Dollin from St Marys. He had fought at Gallipoli and in France and after his return to Australia worked in the small arms factory at Lithgow. He died of the flu in April 1919. Another returned Penrith soldier was Cecil (Dan) Hamilton. Although, he had fought and was wounded at Gallipoli, he succumbed to the deadly flu at Paddington. Other returning local soldiers were held in quarantine until the authorities thought it safe to release them. Nurse Dorothy Muscio, the daughter of Bernard and Eliza Muscio of Orchard Hills contracted and survived the flu while working at the quarantine station in late 1918. By the end of 1919, she was relief nursing at Taree.

People with family and work associations with the district were reported in the local newspaper to have died from the flu. Hilda (Long) Thurlow and Ada Bragg were both young married women with children who had grown up in Penrith. Ada died along with her newborn child and an older daughter. Husband and wife, Frank and Ada Masters, formerly of Penrith died of the flu at Lithgow, a day apart. Dr William Elworthy who had practiced in Penrith until early 1910 had also succumbed to the flu.

The Penrith Council area had thirty-nine reported cases between 10 April and 31 July with eighteen recorded deaths. The first recorded case of influenza in the registers in Penrith was twenty-nine-year-old John Houghton from Valley Heights on 10 April 1919. He was admitted to Nepean Cottage Hospital. The next case was not until 29 May when Denis McAuliffe in Belmore Street fell ill. The vast majority of cases were recorded between 22 June and 31 July when thirty-three cases were recorded. Those deaths recorded were: William Gersbach (Castlereagh Street), Matilda Field (High Street), Harry Horstmann (Emu Plains), William Burgess (Station Street), Claude Purcell (Henry Street), Maude Johnson (Cranebrook), Thomas Johnson (Cranebrook), Sarah Adams (Warwick Street), Arthur Hodges (Lemongrove Road), Kathleen Potter (Henry Street), Eva Johnson (Riley Street), Ada Paul (Riley Street), May Schneider (Cranebrook), Mary Glasscock (Woodriff Street), Alfred Thomson (Tindale Street), Harry Best (Lethbridge Street), Arthur Withers (Lemongrove Road), Eva Chaney (Wentworth Falls). Arthur Withers, an electrical mechanic with the Penrith Post Office had attended the Peace Day celebrations on 19 July in Sydney. The following day he fell ill. He died a week later, leaving a wife and three small children, the youngest two months old.

The Johnson family living at Castlereagh lost five members within two weeks. Sixty-one-year-old Thomas Johnson died on 27 June and his twenty-nine-year-old daughter Maude the following day. Another daughter Ada Florence Paul died on 4 July and her daughter, week old Gwendoline on 8 July. Another daughter Eva died on 5 July along with her newborn daughter Florrie. May Schneider another daughter died on 11 July. This made five members of this family to die from the flu. Two of these were young women who had given birth prior to dying. Their newborn children also died within days. The government assisted Thomas’ wife Emma and her family with the funeral expenses.

In the Castlereagh council area diphtheria and scarlet fever mostly in children were the most prevalent diseases before and after the flu epidemic. Castlereagh Council reported three cases between 5 May and 24 June. They were Thomas Pearce, Percy Farlow and Flora Devlin. One death is recorded in the Castlereagh infectious diseases register – Flora Ellen Devlin, the wife of Castlereagh Council town clerk Arthur Devlin. Also, Sarah Adams, the wife of councillor John Adams of Nepean Shire died of the flu after caring for her ailing family.

Between April and July 1919, ten cases of pneumonic influenza were reported at St Marys, mostly all living in Victoria Street (the Great Western Road). Three deaths were recorded: Arthur Tolhurst, Daisy Schmidt and Ethel Thompson. After 18 July no more cases were reported.

By the end of July the influenza epidemic had passed and again all council received the usual cases of diphtheria, scarlet fever and enteric fever. Life went on without the loved ones not only lost during the war, but also from the devastating effects of war from disease.

Many of the sick were taken to Nepean Cottage Hospital, which would later become Governor Phillip Special Hospital.

List of people with influenza in the Penrith area.

The Public Health Act came into force in 1896, instructing municipal councils to keep a register of Notifications of Infectious Disease. Local doctors notified the Council when an outbreak occurred. The first entries in Penrith Council’s register were for 1898 and there were thirty-four cases of scarlet fever, three of typhoid, three of enteric fever and ten cases of diphtheria reported. Council kept records for infectious diseases until as late as 1983.

Castlereagh - Register for Notification of Infectious Disease 1910s

Penrith - Register for Notification of Infectious Disease 1898- 1902

Penrith - Register for Notification of Infectious Disease 1919

St Marys - Register for Notification of Infectious Disease 1890-1918

St Marys- Register for Notification of Infectious Disease 1919